MIND THE GAP: A $20bn GROWTH FUNDING GAP

INTRODUCTION

This report underscores a projected $20 billion funding gap in MENA in the coming period. In the past five years, the abundance of early-stage investors helped position MENA technology ventures on the exciting trajectory they have today. As these companies graduate to advanced levels, the scarcity of growth-stage capital poses a risk to the sustainability of this momentum. We believe MENA can benefit from more venture capital funds specializing in growth stage, and the role of government is crucial to continue development further up the technology investment value chain.

The MENA venture capital sector experienced a significant breakthrough in 2018 when a handful of institutional investors began actively supporting numerous technology companies. Over the past five years, this momentum has resulted in funding more than 2,000 startups, with over $9.0 billion in equity investments. Presently, there are ~220 companies that have successfully secured Series A or later funding rounds, which are referred to as 'growth-stage' in this report [1]. This marks a historic milestone as the Saudi Arabian and overall MENA VC ecosystem enters its growth-stage phase for the first time.

In terms of funding requirements, the growth-stage segment of ventures demands ten times more capital compared to its early-stage counterpart. However, despite this higher capital requirement, the risk profile of growth-stage ventures is significantly lower. This presents an excellent opportunity for investors to deploy substantial capital into companies with a lower risk profile that can deliver attractive returns within a relatively short time frame of 2-5 years.

So why is there a gap in the availability of growth-stage capital today in MENA? The average AUM of a growth-stage VC fund is much larger than that of an early stage fund, meaning that growth-stage fund managers need to raise from institutional investors such as sovereign wealth funds (SWFs), pension funds, endowment funds, and the likes, as opposed to early-stage funds that mainly target high-net-worth individuals (HNIs) or family offices. However, such institutional investors have rigid internal policies that prioritize capital allocation to funds showing a proven track record in terms of exits and realized returns. Such a track record does not exist yet for MENA growth-stage funds, simply because the industry is still too young and has yet to see the necessary number of materialized exits. A typical startups’ cycle from inception a fund-returning exit is typically 8 years, and most MENA success stories have not existed for that long today.

On one side, more capital is needed to fuel growth-stage companies and enable them to achieve successful exits, and on the other side, successful exits are needed to generate the positive track record that would allow VC investors to raise additional capital. How can we break such a detrimental circular dependency? The ignition of a new industry is one of the clear cases for government intervention. Bridging the growth-stage funding gap would represent the final step in the efforts of MENA governments to complete the activation of a thriving tech venture ecosystem. The emergence of a pioneering cohort of successful technology ventures will establish the track record necessary for private investors to confidently allocate capital, enabling the self-sustainability of the ecosystem.

1. MENA has successfully ignited its technology ecosystem

Inception is the most difficult phase of establishing a thriving innovation ecosystem. This is a time when there are no successful cases to serve as role models and inspire future founders; experienced talent is limited because of the lack of technology companies that make them thrive. Funding is discouraged by the absence of proven successes. Regulation is often unfavorable or simply ignoring of the needs of tech business models. The potential acceptance of technology from consumers and businesses is unknown. This long list of challenges needs to be addressed simultaneously.

The nature of the tech entrepreneurship ecosystem requires a number of enablers to be in place and develop in sync. Therefore, kicking off a new innovation ecosystem is a very complex job. You need to attract and inspire entrepreneurs, devote effort and funding in incubation and acceleration activities, set-up a regulatory framework and incentives to stimulate the start-up of new businesses, foster the formation of a community through events and public relations, and fund a number of local early-stage VCs.

Key drivers of innovation ecosystem - STV framework

Saudi Arabia, alongside a majority of other GCC countries, has successfully executed these steps under decisive leadership that launched a comprehensive series of initiatives to stimulate the ecosystem.

Between 2018 and 2022, these efforts resulted in more than 2,000 MENA ventures that have received $9.0bn+ in equity funding. Of those, 220 are in the growth-stage phase today, i.e. ones that have raised a Series A or above funding round and are presumably looking to raise a Series B or above round. In that same period, Series B and later rounds represented only 4% of the total funding rounds conducted, and accounted for 49% of total capital deployed [2]. As we will discuss later in this report, this is far below the share of growth-stage funding in developed ecosystems.

2. There is a strong pipeline of MENA growth-stage companies

As the MENA ecosystem is maturing, the number of growth-stage companies has increased exponentially. Today, 220 startups have raised Series A+ rounds, of which we see ~160 that are active in the market [5]. This trajectory will continue to go upward in the next few years as the increasing number of start-ups funded in the last 5 years graduate to the late-stage phase.

Number of active MENA ventures having raised Series A and above, 2017-20225

Tech companies have been able to raise larger and larger rounds of funding on the back of a solid growth of their fundamentals, in many cases having achieved more than $100M in topline. This is the case for six of the STV portfolio companies which grew their revenues from a few millions at the time STV invested in them to more than $100m in annual revenue each.

STV Portfolio Revenue Growth (6 largest companies with of $100m+ LTM/ARR)

The MENA growth-stage companies span across several sectors with the majority of them focused on eCommerce, FinTech and Logistics. These sectors have the largest TAMs in MENA and are the ones with the highest likelihood to accommodate large-sized winners.

MENA Companies that raised Series A and above, end of 2022, split by sector [6]

Another sign of the ecosystem maturing and entering the growth-stage is the increasing activity in tech exits. Tech acquisitions have been on the rise in recent years, with a total of 190 acquisitions between 2018 and 2022. To date, we’ve seen 4 MENA tech IPOs, with a number of additional MENA growth-stage companies having publicly announced their plan to prepare for an IPO, including several STV portfolio companies such as Tabby, Floward, Trukker, and Unifonic

Select headlines of MENA tech companies announcing IPO plans

3. MENA needs ~$25bn in growth-stage funding

Venture-backed companies need to raise 10-20 times more capital during their growth-stage phase compared to when they were early-stage [8]. This is a time when the business model is proven and the focus moves from experimentation to scaling. This need for additional and larger capital injections allows companies to hire experienced executives, expand geographically, grow working capital, establish M&A initiatives, and many more levers that scale these rocket ships to become long standing, sustainable, and profitable companies.

Average deal size by stage and country, USD millions [8]

While the capital needed in growth-stage phases is much higher, the risk profile is significantly lower compared to the early-stage startups. This represents a great opportunity for investors to deploy a large amount of capital on lower risk companies that can deliver attractive returns in a relatively short time frame, as the exit typically materializes in a shorter time frame of 2-5 years.

Furthermore, large rounds are becoming more frequent as companies move from Series A to later series. Indeed, the number of funding rounds larger than $30m has constantly grown in MENA, moving from 5 in 2020 to 22 in 2022, and this trend is only set to continue. The number of $100m+ especially has seen a large spike in the last couple of years, with the first one occurring in 2020, as the region sees more and more Series C+ funding rounds.

Now that MENA is entering the growth-stage season, the relevant question becomes: is the available growth-stage capital sufficient to fuel emerging winners and enable them to cover the last mile until the exit? Using three different methodical approaches, we estimate a need of ∼$25bn for growth-stage funding in MENA in the next 5 years. This capital is required to enable the achievement of MENA full potential in the production of successful tech companies.

Method 1: VC deployment projections based on GDP size and ratio

In countries where the VC industry is well developed, the yearly deployment of VC capital is between 0.2% and 1.0% of their GDP, and the share of growth-stage deployment can be as high as 90% in some countries. In contrast, the average VC deployment as a ratio of GDP for the three MENA countries with the highest VC activity is only 0.11% (about half of the equivalent in more developed LatAm ecosystems), and their average share of growth-stage capital is less than 50%.

VC deployment as a % of GDP by country, 2018-2022 [11]

VC deployment share by stage and country, 2018-2022 [12]

In the chart below, we project the VC capital deployment in MENA assuming that the VC deployment to GDP ratio will reach 0.33% in 2028 and that the split between early-stage and growth-stage will be 25% to 75%, equivalent to what we observe in developed markets. This shows that MENA needs about $39bn in VC deployment between 2023 and 2028, of which $26B in growth-stage capital.

VC deployment in MENA, actual values and projections (USD Billion) [13]

Method 2: deployment projections based on potential MENA Unicorns

Based on our previous STV Insights report - “From start-up to IPO” - MENA has the potential to produce an additional 40 unicorns by 2030. Based on global benchmarks, each unicorn on average requires ~$270m of total funding [14]. This translates to a required total of $10.8bn to produce an additional 40 unicorns besides. Moreover, we expect a 40% success rate for growth-stage companies raising much larger rounds. This translates to a total of $25bn in funding requirement.

Method 3: graduation of ventures across the funnel

In new VC ecosystems, initial investments favor early-stage ventures. As successful early-stage companies mature, growth-stage opportunities arise. In MENA, companies typically take 8 years from startup to exit. The rise of early-stage companies in 2018 sets the stage for a new era of growth-stage companies today, 5 years later. This trend will likely continue as post-2018 companies advance. The table below shows averages in VC ecosystems similar to and including MENA.

Startup fundraise statistics and trends [15]

The graduation rate measures the share of start-ups moving through the fundraising funnel from one stage to the next. A company can exit the funnel either because it defaults, becomes self-sustainable, or records a successful exit.

For every 100 companies that close pre-series A rounds, 37 progress to Series A, 12 advance to Series B, 5 reach Series C, and 2 reach Series D and beyond, resulting in a cumulative total of 157 funding rounds. Companies that navigate through each stage of this process typically achieve an average total funding amount of $271m. Ultimately, an estimated $2bn in funding is required to facilitate the growth journey of 100 pre-series A companies, 80% of which allocated to growth-stage rounds and 20% to early-stage.

Illustration of funding needed for startups to go through the full fundraising funnel

Considering that MENA over the last 5 years on average had 468 startups born and raised their first round of funding each year, we estimate that the yearly funding needed will be $9.5bn of which $7.6bn per year would be allocated for growth-stage companies. Below we report the funding projections, considering the 158 MENA growth- stage companies existing today and assuming that on average the region will continue to produce 468 new start-ups yearly.

Projected MENA funding needs, early-stage and growth-stage

4. There is a large gap in MENA growth-stage funding

If the growth-stage funding needed in the next 5 years is about $25bn, how much is the dry powder currently available in MENA? To answer this question, we looked at the different categories of investors and we estimated the dry powder of each of them.

MENA growth-stage VC investors and capabilities

1. MENA Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs)

MENA SWFs invest in growth-stage tech companies either through dedicated VC funds/ divisions (e.g. Sanabil under PIF, and Mubadala Ventures under Mubadala), or directly from the main fund (e.g. ADQ). Despite the investment activity of these players having been quite sporadic to date, they have sizable AUMs and the dry powder necessary to potentially become more active going forward. The estimated dry powder for this category of investors that we arrived at was based on their maximum growth-stage VC deployment in a single year.

2. MENA growth-stage VCs

Funds that focus on growth-stage have typically at least $300m of capital commitments that enable them to allocate up to $45m to a single portfolio company, giving them the ability to lead rounds larger than $100m and double down on their performing portfolio companies. In MENA, only two GPs have that capability: STV, who manages a $800m fund, and Impact46, who manage a number of growth-stage and single-asset funds. Both funds are focused on MENA technology companies and are sector agnostic. The estimated dry powder of these funds is based on their fund sizes, new commitments, and estimated capital deployed.

3. Global growth-stage VCs investing in MENA

These are VC growth-stage funds that either have a mandate focusing on other regions but from time to time invest opportunistically in MENA, such as Sequoia Capital India & SE (now Peak XY Partners) or are funds with a global mandate such as SoftBank, General Atlantic, Prosus and Tiger capital. Estimated dry powder for these investors is based on fund sizes, deployed capital, and ratio of MENA VC deployed capital to total deployed VC capital.

4. Other non-VC MENA investors

These investors are MENA based or they are active in MENA across a broad range of asset classes. Their attention to technology ventures could vary over time as the VC asset class is competing with others. Furthermore, while some of them possess capabilities that are relevant also to growth-stage tech ventures such as Gulf Capital, Invest Corp and Kingdom Holding, others are more generalist such as family offices or investment brokers. Estimated dry powder for these non-VC focused investors is based on AUMs and ratio of VC deployment in MENA.

Tech growth-stage MENA companies need investors with both, consistent focus and specialized capabilities. The consistent focus is necessary to ensure continuous availability of capital and to avoid the risk of such capital being diverted to competing asset classes from time to time. Specialized capabilities are needed to price, support value creation and steer emerging winners toward successful exits.

The only two categories of investors that have such attributes are the VC arms of regional SWFs and the regional growth-stage VCs. Thanks to its $800m fund, STV has been the most active with 27 growth-stage rounds lead between 2018 and 2022. The activism of the venture arms of regional SWFs have been largely sporadic so far but has recently shown more consistency. On the other hand, the non-MENA growth-stage VCs returned to focus on their core markets during the turbulent market conditions in 2022 after having conducted a few investments in 2021, further increasing the gap in available growth-stage capital. Other non-VC MENA investors played a significant part in temporarily bridging that gap , but it is still unclear how much focus they will continue to dedicate to the growth-stage tech segment.

In the chart below, we report our estimate of the $4.2bn dry powder currently available to MENA growth-stage companies. Compared to the $25bn funding need, this means that the market is experiencing a $20bn+ funding gap.

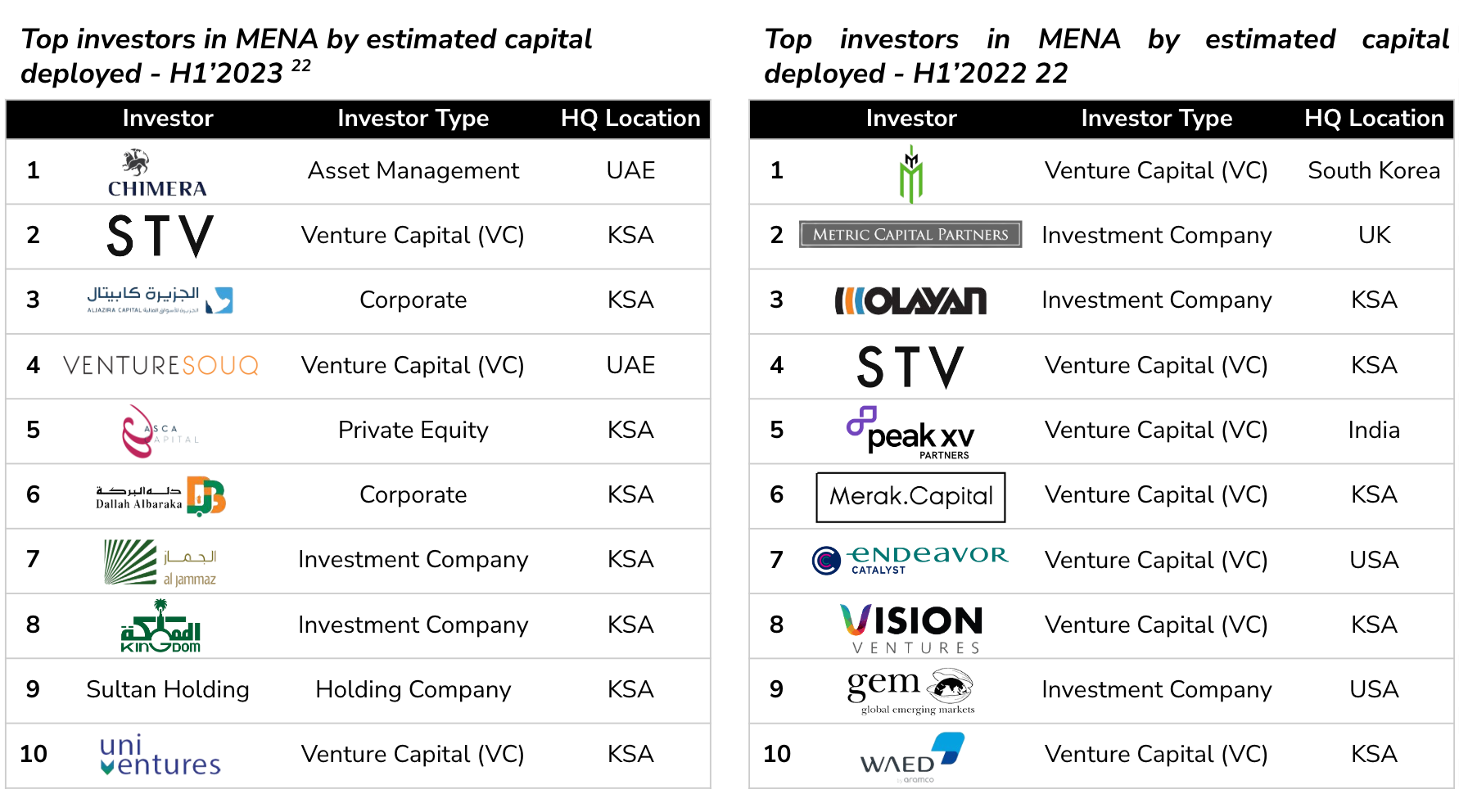

In 2023, the funding gap in the MENA region is already having clear effects that are prohibiting the region from reaching the full potential outlined in Chapter 3. Funding in the H1’2023 plummeted by 42% compared to the same time in 2022. Not only that, but the number of active investors also decreased by over half, a 55% decline to be precise.

MENA Funding by Half Year, 2019-2023 [18]

A major reason for this drop is that international investors, who were quite active in the region previously, have retreated from the region. These investors played a big role in 2022, making up 50% of investors in late-stage deals. But by the first half of 2023, their participation dropped to only 28%. [19]

An interesting shift is seen when we zero in on the top contributors. In H1 2022, the top 10 investors, ranked by their estimated deployed capital by Magnitt, were responsible for 26% of the total deployed capital. Fast forward to H1 2023, and this number skyrocketed to 62%. However, the composition of these top investors reveals more. In 2022, of these leading 10, only 4 were based in MENA and 7, i.e. majority, were VC funds. This year, in a telling turn, all top 10 investors are MENA-based. But, notably, only 3 of them are VCs, with STV being the only investor that retained its top 10 ranking in both years. [20]

Active Investors in MENA Startup Rounds [21]

Local investors, ideally positioned to bridge this funding gap, face a liquidity challenge. The available 'dry powder' or immediate funds are limited, constraining their ability to make substantial investments. It's a precarious balance: with international investors taking a step back and local investors facing constraints, the funding ecosystem staggers.

Worldwide, unicorns typically count 3 growth-stage investors among their shareholders. On average, VC funds manage 20 companies in their portfolios, with ~20% of these achieving the returns that align with the established power law VC fund pattern. Considering our earlier projection of generating 40 more unicorns in MENA, this underscores the requirement for at least 10 growth-stage VC funds in the market.

Average global unicorn-investor dynamics [23]

5. Government can play a critical role in bridging the gap

As previously mentioned, growth-stage VC funds need to raise capital from institutional investors such as SWFs, pension funds, endowment funds and the likes. However, such institutional investors have quite rigid internal policies that prioritize capital allocation to funds showing a proven track record in terms of exits. Such a track record is not available for MENA growth-stage funds, simply because the industry is still too young. So, on one side, more capital is needed to fuel growth-stage companies and enable them to score successful exits. On the other side, successful exits are needed to generate a positive track record that would allow VC investors to raise additional capital. Who can break such a detrimental circular reference? The ignition of a new industry is one of the clear cases for SWFs and Governments intervention who can play a pivotal role without distorting the market.

In a developed ecosystem, the private market will solve both issues, but in a nascent ecosystem such as MENA this will not happen. The main bottleneck is the lack of track record on exits that discourages private investors to deploy capital into growth-stage funds. The role of the public sector becomes critical. A number of initiatives can be considered to address this issue.

The public sector needs to inject more capital into MENA growth-stage funds. This responsibility can be assigned to different categories of capital allocators:

Public Funds of Funds

SVC and Jada played a critical role by allocating on average $10-30 million to early-stage MENA/ Saudi funds. Over time they have developed the capabilities to conduct rigorous due diligence on GPs to guide their development, and have gained a deep understanding of the ecosystem. They are well placed to fulfill a similar role with growth-stage funds by increasing their allocation to $100-300m per investment.

2. SWFs

SWFs could start directly allocating funding to growth-stage funds. The larger size of the allocation compared to the early-stage funds is more compatible with the SWF’s typical ticket size. Furthermore, a direct collaboration between SWFs and VC growth-stage investors could be mutually beneficial as the SWF could gain better access to successful tech ventures that could be further elevated with their support in the context of an IPO exit or global expansion.

3. Pension funds

Pension funds are among the most relevant investors in VC globally. In most of the GCC, pension funds do not have the mandate to invest in MENA VCs, and on the contrary in some cases they are prohibited from doing so. Today, MENA VCs represent an attractive asset class. Furthermore it would be sufficient to have a minimal allocation of the huge AUM managed the regional pension funds to move the needle for the VC industry and start building long-term sustainable relationship between regional pension funds and regional VCs

Public funding sources for growth-stage capital could be allocated to different types of players.

Existing regional growth-stage VCs

The existing regional growth-stage VC are the best positioned to keep steering the ecosystem forward. They have the track-record, the knowledge and the understanding to identify and support the tech ventures with the highest potential.

2. Regional early-stage funds

There is an opportunity to selectively uplift regional early-stage VCs to growth-stage VCs by providing them with additional funding to follow-up on their portfolio or helping them to raise a larger growth-stage fund. Early-stage VCs have gained relevant expertise and knowledge and providing them with the necessary funding to double down on their portfolio winners would help them through an organic transition to the growth-stage segment.

3. Global growth-stage VC funds

Global growth-stage VC funds can bring relevant expertise and potentially also FDI to the MENA ecosystem. Some of them have already sporadically invested. They could be further incentivized to establish a permanent office in the region and to deploy within the region the capital committed by Government funds.

Growth-stage investors and funding sources

6. Conclusion

In light of the evident potential and progress of the MENA tech ecosystem, which is well ignited and poised to produce several successful technology champions, the pressing $20bn funding shortfall cannot be overlooked. While the region's foundation is solid, this financial gap threatens to stall the momentum. It's time for local specialized investors, in tandem with government support, to champion this cause. By actively bridging the funding gap, we can ensure that MENA's promising trajectory isn't merely maintained but accelerated, cementing its place as a global tech powerhouse, and placing the region on the short list of the most attractive and innovative ecosystems.